The introduction of the game coincided with the High Middle Ages

,

just before the Late Middle Ages, which began with the crisis of the 14th century.

It was then that the last and most prominent medieval periods of the renaissance

took place, with the most notable influences on chess being the Ottonian renaissance

(continuation of the Carolingian), and the Gothic pre-renaissance of the 12th century,

with the revitalisation of trade, the emergence of the bourgeoisie and the consolidation

of the Christian kingdoms. The period was interrupted in the 14th century by the Black Death

epidemic.

The spread of the Shatranj in Western Europe is archaeologically present in several places. In the 10th century the luxury pieces were mainly of glass, of Muslim manufacture, and the simpler ones of bone. Beginning in the 11th century, the pieces again took on a figurative form, as they had done in Persia before the Muslim domination. In the 12th century figurative pieces began to become common, but they still shared space with abstract symbolic ivory pieces, that now incorporated engravings, sometimes decorative, but the tendency was to represent the meaning of the piece. Thus, in the 13th century the symbolic pieces characteristic of the Islamic Shatranj, still present in Europe until the end of the 14th century, practically disappeared.

In the Late Middle Ages, and after overcoming the crisis caused by the Black Death in the 14th century, the reform of the game in the 15th century coincided with the emergence of the rich merchants and the bourgeoisie, patronage and the prelude to the Renaissance. The nobility lost importance in favour of the king and the courtiers, so that soon the knowledge of the game was part of the knowledge required of a courtier, emulating the indications of the ancient Muslim sages.

-

Medieval period of warming (950 - 1250)

The Medieval period of warming, also known as the Medieval climate anomaly, was associated with an unusual temperature rise roughly between 950 and 1250 CE. For about 300 years, these new climate conditions changed ecosystems and radically altered human societies.

As northern Europe became warmer, the cultivation boundaries were higher and further north, so agriculture spread and generated food surpluses. At the time, England was warm enough to support vineyards, centralised governments in Europe were becoming stronger, people no longer needed fortifications to protect their once limited arable lands, and many people left seeking new lands.

With sea ice and land ice in the Arctic shrinking with the rising temperatures, new lands became accessible and Vikings travelled farther north than before. The expansion of the Norse culture across Iceland into southern Greenland, and their ultimate establishment of isolated settlements in Newfoundland, occurred during this time.

The early 13th Century marked the beginning of the conquests of Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes. An abundance of moisture would seem to provide the horsepower for the rapidly growing Mongol Empire. The Mongol soldier typically had five steeds at their disposal. With a large army, that quickly translates into huge herds and a huge need for grass.

-

The monasteries and manuscripts

Ripoll Monastery Cloister. Foto: José Luis Mieza, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia CommonsThe importance of the monasteries in producing copies and translations of existing classical works is well known. The invasions of the Western Empire by the Nordic peoples that began in the early 5th century destroyed the imperial libraries spread over much of Italy. Many of their volumes, containing the great Latin classical tradition, were preserved in private libraries. Important repositories of classical books together with Latin ecclesiastical texts were established in Christian communities.

Throughout the Middle Ages, from the foundation of Montecasino (529) until the 15th century, the libraries of Western Europe were exclusively ecclesiastical, belonging to monasteries or cathedrals, and, from the 13th century onwards, to universities. The Benedictine rule, with its prescriptions obliging reading and writing, laid the foundations of the scriptorium and the library that existed in all the monasteries that the order spread throughout Europe.

It is in the monasteries that we find the first reference to chess in the West,

Versus de scachis

, in the Benedictine abbey of Einsiedeln (Switzerland), with strong links to the Ottonian dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire, who had a relationship with Gerbert of Aurillac, Pope Sylvester II, who studied at the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll.With almost no communications in the Late Middle Ages and very little in the High Middle Ages, communications between monasteries were very important, and translations from the monastery of Ripoll were used, for example, in the abbey of Reichenau, on Lake Constance. We must think that practically until the beginning of the 12th century, and the revitalisation of trade in the 13th century, the usual mode of travel was between monasteries, rather than between towns.

The situation in the East dragged on for a few centuries, and from Constantine to Justinian several libraries were organised, in Asia Minor, Alexandria, Palestine, Athens, the monasteries of Mount Athos, and above all, the Imperial library in Constantinople. These libraries suffered multiple fires and invasions, usually destructive. The imperial library was the most important, with some 100_000 copies. But after two major fires in the 5th and 8th centuries, it was plundered by the Croatian Franks and Venetians during the Fourth Crusade in the early 13th century. The Imperial Library, a centre for the preservation of mainly Greek writings, disappeared definitively with the invasion of Constantinople in the 15th century, although it is still the most important source of Greek classics that have survived to the present day.

Even considering the importance of Constantinople, with an important task of conservation and copying of manuscripts for their preservation, it was not an important centre for the generation of new documents, nor for the dissemination of existing ones, as it did not have a school or university, and there is no record of it being a public library; the Neoplatonic school in Athens was closed and its scholars persecuted by Justinian. The contents generated by the Eastern Roman Empire since Justinian were very meagre. For example, chess is considered to have been played in Constantinople, and some testimonies attest to this, but references are practically non-existent. By the 10th century, Damascus, Baghdad or Córdoba were of greater cultural importance, as they had accumulated most of the originals, which were copied in Arabic, and were the centres of cultural production and dissemination.

Estàtua d'Al-Suli en Aixkhabad (Turkmenistan) Foto: https://ruchess.ru/The Sassanid empire (226-651) had three centres of education, at Ctesiphon, Resaena, but mainly the academy of Gundeshapur, which became the intellectual centre of the empire in the time of Khosrow I, offering refuge to the Hellenistic intellectuals of the Neoplatonic school of Athens, persecuted by Justinian I in 529. This school also made many translations into Pahlavi, Sassanid Persian.

In 825, with Persia under Muslim rule, the

House of Wisdom

orGreat Library of Baghdad

was established, emulating the academy of Gundeshapur; in fact, the academic centre of Baghdad drew on the scholars of Gundeshapur, beginning the rapid decline of the Persian academy. TheGreat Library of Baghdad

is considered the first university in history, and acted as a centre for the dissemination of Islamic thought during the Golden Age of Islam. Its scholars also acted as civil servants, serving as physicians, architects and political advisors, among others. It was destroyed by the Mongols during the siege of Baghdad (1258).Many well-known scholars wrote books on the Shatranj in this golden age:

- Al-Suli, with the complete name Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyā ibn

al-'Abbās al-Ṣūlī

(أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن العباس الصولي) wrote:

- Kitāb al-Shiṭranj al-Nisḥa al-Awala (كتاب الشطرنج النسحة الاولة)

First version of chess book

. - Kitāb al-Shiṭranj al-Nisḥa ath-Thānīa (كتاب الشطرنج النسحة الثانية)

Chess book second edition

.

- Kitāb al-Shiṭranj al-Nisḥa al-Awala (كتاب الشطرنج النسحة الاولة)

-

Al-Lajlaj, alumne d'Al-Suli, with the complete name

Abu al-Faraj Muhammad ibn Ubaid Allah al-Lajlaj (ابو الفرج محمد بن

عبيد الله

اللَجْلاج)

wrote Manṣūbāt al-Shiṭranj (منصوبات الشطرنج)

Chess positions

. -

Al-Adlī (العَدْلى): Kitāb al-Shiṭranj (كتاب الشطرنج)

Chess book

. -

Al-Rāzī (الرازى): Kitāb latīf fī al- Shiṭranj (كتاب لطيف في

الشطرنج)

A good chess book

.

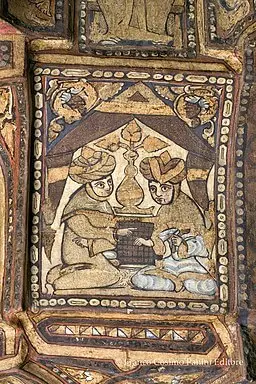

Miniature of the Al-Hariri Maqamat (collection of tales)

Credit: Zereshk, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsFrom the 9th century onwards, an important network of libraries spread throughout the Islamic world: Baghdad, Cairo, Alexandria, Cordoba, Toledo and Granada. The library in Cordoba had as many as 400_000 copies in the 10th century, while the Cluniac library in the 11th century had only a few hundred volumes; hence the great importance of the Toledo School of Translators in the 12th and 13th centuries, who translated many Arabic manuscripts. Many Jews also acted as translators, and thus would be a transmitter of the cultural and scientific legacy of the Arab world to both Jews and Christians. In the West, the work of Alfonso X of Castile, mainly a compendium of knowledge of Muslim origin, is well known, as the Islamic contents concerning the Shatranj and other games were quite extensive, mainly from writers of Persian origin.

As early as the 13th century, Paris was the first city to have a large commercial exchange of manuscripts, with manuscript producers commissioned to make specific books for specific people. Paris had a large population of wealthy literate people, enough to support the people who produced the manuscripts. This medieval period marked the shift in manuscript production from monks in monasteries to booksellers and scribes who made a living from their work in the cities. In the 11th and 12th centuries chess became popular among monks, nobility and clergy, but in the 13th century there are references to its use by crusading soldiers, thus being a further factor in the game's arrival among the wealthy merchants and cultivated professionals who began to appear in the cities.

The 13th and 14th centuries brought a profound change to medieval libraries. Universities and university libraries appeared, although they did not really come into their own until the Renaissance. Private book collections increased greatly. In Italy, the first humanists, Petrarch (1304-1374), Boccaccio (1313-1375) and, especially, Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459), travelled through the ancient abbeys and interacted with merchants from the East in search of classical Greek and Latin texts.

- Al-Suli, with the complete name Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyā ibn

al-'Abbās al-Ṣūlī

(أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن العباس الصولي) wrote:

-

European immigration in Islamic lands

Inside the Mosque of Cordoba. Crèdit: Timor Espallargas, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia CommonsMany Islamic cities were great centres of knowledge and prosperity, and there was great religious tolerance, so that travel to Damascus, Baghdad, and Cordoba was common. These could be considered cultural journeys, and the prosperity of these cities encouraged many to take up residence, with frequent conversions of immigrant Christians to Islam; a simple phenomenon of cultural and economic immigration to the rich, cultured and developed cities of Islam.

In the 10th century, during the time of Caliph Abd-ar-Rahman III (891-961) and his son Al-Hakam II (915-976), al-Andalus enjoyed unprecedented economic and cultural splendour, with its centre in Córdoba. There was a high degree of tolerance so that philosophers, scholars, artists and scientists of various origins entered his courts. Al-Hakam II created the richest and most important library in Europe in Córdoba. Translators translated thousands of Greek and Latin works into Arabic. The caliphate, which became an important state at the end of the reign of Abd-ar-Rahman III, maintained diplomatic relations with the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire. The caliph maintained a permanent delegation in Baghdad to copy or acquire any volume that could be published, and also maintained relations with delegations in Constantinople, Alexandria and Damascus, cities also very rich in culture, which enabled him to continue to enrich the library in Córdoba.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, many Christian scholars travelled to Muslim lands to learn science. Prominent examples are Leonardo Fibonacci of Pisa (1170 - 1250), important mathematic, and Adelard of Bath (1080 - 1152) who made Latin translations of many important Arabic scientific works, including ancient Greek texts that only existed as translations in Arabic, and were thus introduced to Europe. Another case was Constantine the African (1017 - 1087), one of the introducers of Arabic medicine to Europe. In the 11th to 14th centuries many European students attended Muslim centres of higher learning, similar to Western universities.

-

Pilgrimage

Another motive for Christian visits to Islamic lands was pilgrimages to the Holy Land, Palestine. Constantine I in 330 moved the capital of the empire to Byzantium, and built Christian places of worship in Jerusalem, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In 603, Pope Gregory I commissioned the construction of a hospital in Jerusalem, which was part of the Eastern Roman Empire, to serve and care for Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land (a hospital was then a type of hostel). In 614 the Sassanid Empire conquered Jerusalem, until it was recaptured in 629 by Emperor Heraclius, but Byzantine Jerusalem was finally conquered by the Arabs in 638. In 800, Charlemagne enlarged the Jerusalem hospital, and added a library.

From the 4th century onwards, new pilgrimage routes were established through the lands of the Eastern Roman Empire, routes that had not been common until then, as Christians had been persecuted. These routes for many centuries represented an important cultural flow through Constantinople. Later, towards the end of the 11th century, these routes were used for the Crusades.

Another important pilgrimage would be the Roman routes, to reach Rome. They had different variants, with the facility of often still existing Roman roads, including bridges to cross the most difficult river crossings.

As can be read in the section on Castile and León, the pilgrimage along the Way of St. James also began to be an important cultural route for Europe from the 11th century onwards. It contributed to communication between monasteries, and from the 12th century onwards it was also a route frequented by the nobility.

It was generally in the 11th century that far-reaching commercial activities, hitherto limited in Europe to the activities of the Muslims, the maritime activities of the Eastern Roman Empire and the Viking raids, which were warlike in the west, but more commercial in the east, began to resume. The pilgrimage routes began to be protected by the kings of Christendom, which encouraged them to be exploited for trade.

-

The church

The earliest recorded case of prohibition is the 529 CE ordinance issued by Emperor Justinian of the Eastern Roman Empire, when he closed the Neoplatonic Academy and schools in Athens. It forbade

teaching philosophy

,explaining the laws

andplaying dice

. This was a few years before the arrival of chess in Persia, but the ban may have delayed the entry of chess into the Byzantine empire, where it was called Zachitrion.Islam also had its prohibitions. In 655, Caliph Ali Ben Abu-Talib banned chess because the pieces had idol figures on them. In 680 Islam interpreted the rule as forbidding chess, although the Caliphs themselves played chess and had chess players in their court.

Around 1061 Peter Damian wrote to Pope Alexander II (pope between 1061 and 1073) complaining about the use of chess by clerics as a game that was

dishonest, absurd, libidinous, and a distraction from the duties of the clergy

.By the year 1093, shortly after the

Great Eastern Schism

(1054), the Eastern Orthodox Church condemned chess. The Church eradicated chess in Russia as a vestige of paganism.Around 1115, the emperor Aleix I Comnè was fond of the game. Despite this, it was still censored in the Eastern churches until 1125. John Zonares, a monk who had been captain of the Byzantine imperial guard, issued a directive banning chess as depravity.

Although some popes were fond of chess, such as Gregory VI (pope from 1045 to 1047), Innocent III (pope from 1198 to 1216) or Innocent IV (pope from 1243 to 1254), and the figure of Sylvester II (pope from 999 to 1003) could have been decisive in the spread of chess throughout Europe after his time at the Ripoll Monastery in Catalonia, the various prohibitions and condemnations followed one after the other from the 11th century, when Peter Damian wrote to Pope Alexander II complaining about the use of chess by the clergy.

Another reason for the reluctance to chess in the West may have been its Muslim origin, when in 1095, at the end of the 11th century, there was the declaration of holy war (the Crusades) by Pope Urban II, in response to the request of the Roman Emperor of the East, Alexius I Comnenus, for military aid against the Seljuks. There were already voices criticising chess as unsuitable entertainment for soldiers, and in fact the reason for this is unclear, but the Knights Templar were banned from playing chess by St Bernard of Clairvaux in 1128.

The situation dragged on for 500 years, until the game was fully accepted in the 16th century, with Pope Pius IV, of the Medici family, after the Council of Trent, coinciding with the stay in Rome of Ruy López de Segura, then considered the best chess player in Castile. However, in 1551, Tsar Ivan IV, Ivan the Terrible, proclaimed a ban on chess in Russia, which remained in force until the 17th century.

-

Crusades

Map of the First Crusade

1096-1099Original work: Captain Blood at de.wikipedia; Translation: Oxag at fr.wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsFrom the end of the 11th century to the 13th century there was the phenomenon of the crusades, military campaigns, armed pilgrimages and the establishment of new Christian kingdoms, which also had the indirect effect of cultural exchanges, but the forced character determined by circumstances brings them closer to the spoils of war; chess pieces of rock crystal or ivory were often used as embellishments for other pieces, and, despite references, no set of pieces with precious gems has been found.

Although many nobles travelled to the lands of Palestine, the phenomenon slowed down the exchanges that generated trade and peaceful Christian immigration to the lands of Islam. Despite this, it was instrumental in the re-establishment of international trade, and also facilitated rapprochement with some elements of Islamic culture; for example, stories are told of soldiers playing chess in their free time, indicating that chess was already a popularly known game, and the war contributed to its diffusion.

It should also be remembered that crusading routes to Palestine generally passed through the Eastern Roman Empire and Constantinople.

Relations between the Western Europeans (Latin or Franks in the nomenclature of the time) and the Eastern Europeans (Greeks) had been complicated since the Great Eastern Schism that began in 1054, just before the beginning of the crusades. From then on, the Westerners had been hostile to the Easterners, as was evident during the First, Second and Third Crusades. These relations deteriorated further in 1182 (before the Third Crusade), when all the foreigners in Constantinople had been massacred and the Venetian merchants had been expelled by the Byzantine emperors of the Angelos dynasty.

First Crusade (1096 - 1099)

Taking advantage of the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus call for help, Pope Urban II exposed the need for Christians in the West to engage in a holy war against the Turks, who were exercising violence against the Christian kingdoms of the East and mistreating pilgrims going to Jerusalem, and the conquest of the so-called Holy Land.

In the first crusade, the phenomenon of the People's Crusade appeared, mobilising some 100,000 humble people, men, women and children, responding to the papal call. Even with the virtual annihilation of all 30,000 Crusaders who crossed the Bosporus with the help of ships provided by Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, many others reached Constantinople or the dominions of the Eastern Roman Empire without completing their journey, thus bringing the French, Germans and Italians into closer contact with the culture of the Eastern Roman Empire.

In the main church-organized crusade, the Norman forces, who had recently been in conflict with the Eastern empire in territories of the Italian peninsula, were prominent, and the emperor distrusted them. However, this much more organised crusade managed to conquer a large part of Anatolia, Lebanon and Jerusalem, and this first crusade was the only successful one in terms of warfare, although only a small part of it was returned to the Eastern Roman Empire.

Fourth Crusade (1202 - 1204)

Conquest of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 David Aubert (1449-79), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae LatinEmpire, CC BY-SA 3.0, via la Wikimedia CommonsIn 1202 the Republic of Venice had completed preparations for the crusade, which was to attack directly the heart of the Islamic world at the time, the city of Cairo, on papal orders. But many embarked in other ports, and only 12_000 men took part, instead of the 33_500 men budgeted for. Venice demanded the full payment, 85_000 silver marks, but the Crusaders were only able to collect 51_000. This left them in a state of abject poverty, and an economic disaster also for the Venetians, who had stopped their trade for a whole year to prepare for the expedition. The proposal was to change the objective, and for the Crusaders to pay their debts by capturing the Dalmatian port of Zadar.

The city had already been economically dominated by Venice in the 12th century, but in 1181 it had rebelled and sought the protection of the King of Hungary and Croatia. But the king of Hungary was also a Catholic and had offered, at least in theory, to take part in the crusade himself.

The crusaders made a pact with the emperor's brother prince and reached an agreement to help him overthrow his brother. The new emperor, Alexios IV Angelos realised that he did not have enough wealth to pay for the pact, even with the destruction he carried out of priceless Roman and Eastern Roman icons in order to extract the gold and silver. The crusaders, dissatisfied, rioted, and much of the city was burned.

Eventually the Greeks assassinated Alexius IV Angelo, and the new emperor Alexios V Doukas denied the pact with the crusaders and Venetians, who sacked Constantinople. According to a pre-arranged treaty, the empire was distributed between Venice and the crusading leaders, and the Latin Empire was established (1204), and it lasted until Constantinople was reconquered by the Eastern Roman Empire in 1261, which largest rump state is named Empire of Nicaea.

-

The trade

In the early Middle Ages, before the year 1000, Europe was a land of political unrest and lack of security, with a subsistence economy and little movement of goods. Trade was mainly a local phenomenon with no long-distance routes, leaving these activities in the hands of the Eastern Roman Empire, which traded by sea, and above all the Muslim world. Urban markets began to enliven internal economic life from the 9th and 10th centuries onwards, and from the 11th century onwards the first fairs increased internal and external trade. The purchasing power of the more powerful sectors of the population was greatly increased, and they were attracted by luxury goods from the East.

Pilgrimages and crusades would play a very important role in this commercial renaissance, which would manifest itself in the extension and renewal of routes and the volume, number and quality of goods, in the appearance of the first armed associations of merchants, and in the appearance of new fairs and fixed markets.

In addition to the sea routes, there were some land and river routes in continental Europe, many of which are thought to date back to Charlemagne, although there is no written record before the 11th century, when they were of great importance in the Ottonian renaissance, the growth of the maritime republics of the Italian peninsula, and the pre-Renaissance Gothic period of the 12th century.

Section: Martin Jad Mansson provides an excellent detailed map of trade routes in the High Middle Ages, between the 11th and 12th centuries. In the detail of this section we detail some of these routes.

Rutes de comerç

-

Silk Road

Maritime variant of the Silk Road

Radhanites

-

Routes of the Eastern Roman Empire

-

Routes of the Iberian Peninsula

-

Imperial and roman roads and fluvial routes

The Rhône

The Rhine

The Elbe

-

Trade in the Baltic Sea

Amber Road

Volga and Dniéper: Khazar and Varangian routes

-

-

Iberian Peninsula: Castile and Leon

Islamic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula. NACLE, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsThe Iberian peninsula was undoubtedly the main gateway of the Shatranj into Europe, as a consequence of the Muslim presence on the peninsula from the beginning of the 8th century until the end of the 15th century. Even so, it must be understood that in the 9th, 10th, and much of the 11th centuries, the contact of the Christian kingdoms of the peninsula with the rest of Europe was generally too distant to maintain a fluid cultural exchange.

It was practically with the death of Almanzor and the appearance of the Taifa Kingdoms that the timid European contacts of Sancho III of Pamplona began, at the end of the 10th century and the beginning of the 11th century. Prior to this, the Asturian and Vascona resistance was so isolated that it even kept itself culturally separated from the Islamic world, its enemies.

The Way of St. James was an important bridge for cultural exchanges with Europe, but its beginnings at the European level can be dated to the 10th century, with the pilgrimage of some clerics and bishops. The great expansion and popularisation took place in the 11th century, coinciding with a more favourable political environment after the death of Almanzor, and the construction of hospitals and improvements to the paths and roads began. The construction of the current cathedral of Santiago began in 1075, the last stone was laid in 1122 and the cathedral was consecrated in 1128.

At the end of the 11th century the kingdom of Castile incorporated Toledo, which by the 12th century had become an important cultural centre, coinciding with the authorities' support for the Pilgrim's Way to Santiago, protecting pilgrims. In the 13th century there was already a large infrastructure associated with the Way, the influx of nobles increased, and the cultural return to the peninsula was already quite significant. After the first years of religious coexistence, with the appropriation of Arabic writings, the Toledo School of Translators created at the beginning of the 12th century a cultural centre of great importance for the whole of Europe. This centre reached its climax in the 13th century, with Alfonso X, who made a great compilation of Islamic knowledge of chess, probably knowledge of Persian origin, incorporating many Castilian contributions.

Thus, the 12th and 13th centuries were the great cultural period in Castile and León, and it was mainly during the 13th century that the work produced by the Toledo School of Translators became important. In fact, although it was closed after the death of Alfonso X, the importance of its work would be maintained over the following centuries.

-

Iberian Peninsula: Catalonia and Aragon

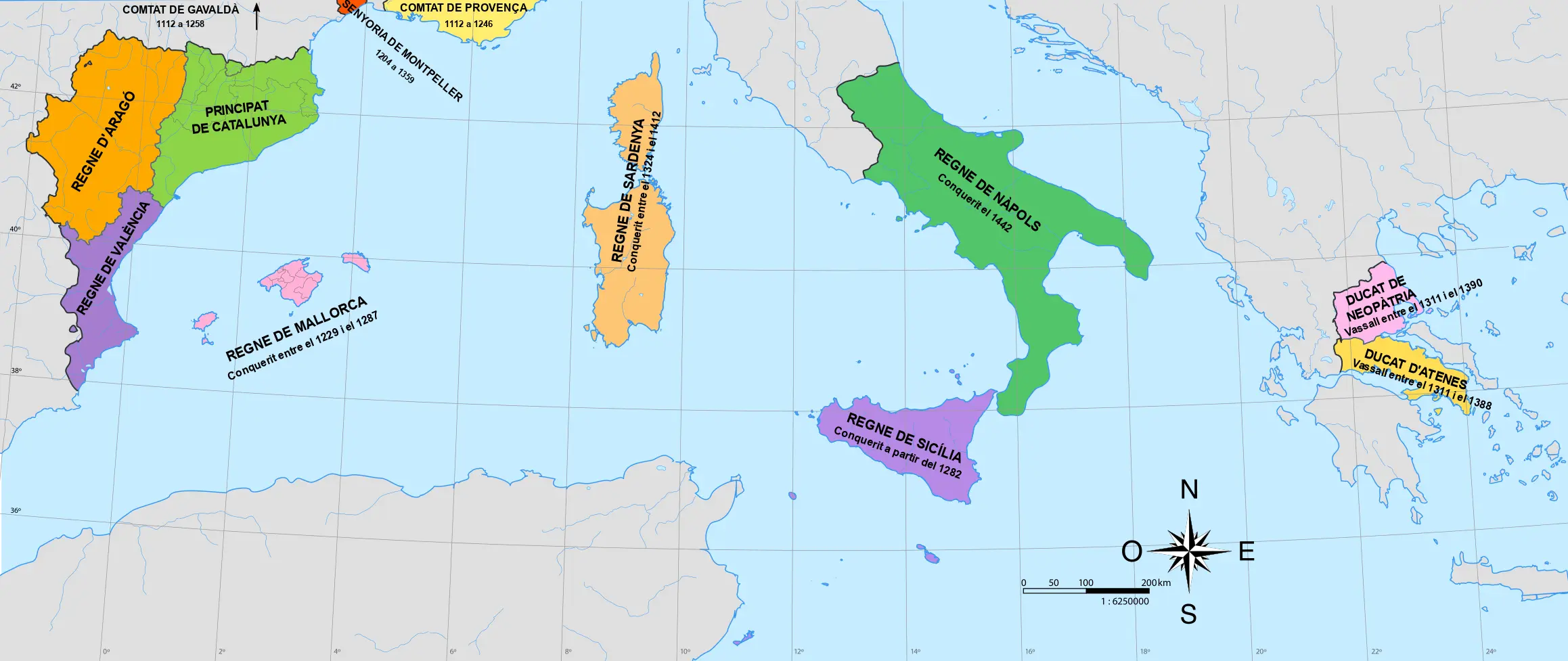

Anachronistic map of the possessions of the Crown of Aragon. Milenioscuro (Original) Indpcatll (Translation), CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsAt the beginning of the 9th century, during the time of the Arab invasions, Charlemagne's empire created the counties of Catalonia and Aragon as border counties to prevent Muslim invasions; they were what was called the

Marca Hispanica

, although they were a group of counties that never had a common political entity. In reality, the kingdom of Pamplona was never dominated, neither by the Visigoths nor by the Muslims. The county of Aragon became a kingdom after the union with the kingdom of Pamplona, thus freeing itself from Frankish vassalage, and at the beginning of the 11th century it freed itself from the vassalage of Pamplona. Catalonia freed itself from vassalage by starting the hereditary system with Wilfred I, and his son, Wilfred II, at the beginning of the 10th century, no longer rendered vassalage to the Franks.We find the first references to rock crystal chessmen in Catalonia, mentioned in the testaments of Ermengol I, Count of Urgell written on the occasion of the military expedition of the Catalans against Cordoba in 1010, which resulted in the sacking of the city. In 1056, in the will of Ermesinde of Carcassonne, other rock-crystal chessmen are also mentioned.

There is also the case of the existence of the rock-crystal set in Àger, and documentary evidence in other places, such as the abbey of Ripoll, or the now lost ones in the cathedral of Roda d'Isábena, or those mentioned in the inventory of the monastery of San Andrés de Fanlo, in Sobrarbe, province of Huesca, Aragón.

-

Italian peninsula and Sicily

Italy in the year 1000 Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

First painting of chess in the West, in the Palatine Chapel in Palermo, Sicily. (1143). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons -

Eastern Roman Empire

Byzantine Empire Original: Varis - Derivative work: Roke~commonswiki, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ivory Queen

Tresor de Saint-Denis,

probably made in Salerno, 11th centurySiren-Com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons -

Khazars, Varangians and Vikings

13th century Swedish queen

walrus ivory.

Foto: Hildebrand, Gabriel

Swedish National Historical Museum SHM (CC BY 4.0) -

Frankish, Carolingian and Romano-Germanic Empires

Equestrian sculpture of Otto the Great in Magdeburg. Furmeyer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Holy Roman-Germanic Empire Crèdit: A.cano.2, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsThere are several legends relating to the court of Charlemagne and chess:

-

Legend of the creation of Tegernsee Abbey

At the court of King Pepin (father of Charlemagne), an unfortunate situation arose when a son of the king killed a son of Otger in a dispute over a game of chess.

The Bavarian brothers and nobles Adalbert and Otger withdrew from the court, returned to their own domains, abandoned secular life and founded the abbey of Tegernsee.

-

The pieces of Pepin the Short

The most historical reference appears to be in a medieval Latin writing, dated to the 13th century, which recounts the donation by King Pepin the Short, in 764 AD, of some pieces of glass inlaid with gold and precious stones to the abbey of Mozac.

The pieces were destined for the transfer of the remains of Saint Austremonius from Clermont-Ferrand to make a reliquary in which the saint's remains were to be kept.

Indeed, Pepin the Short in the year 764, or perhaps Pepin I of Aquitaine in the year 848, had the relics transferred to the abbey of Mozac.

-

Charlemagne's chess legend

There are several legends linking Charlemagne with various existing chess sets, including a legend concerning a reliquary that has little to do with chess, and which seems to date from the 14th century; the legend of this reliquary, in spanish, can be found in the link above.

We incorporate here one of the many legends linking Charlemagne to chess; in fact, there are several chess sets called

Charlemagne's chess

, and we have chosen a modified version of the legend of the so-called reliquary:At a feast on 4 April 782, in Aachen, to commemorate Charlemagne's fortieth birthday, he intended to take on the best chess player in the kingdom, a soldier by the name of Garin the Frank. They used a chess set, a gift from Ibn-al-Arabi, the Muslim governor of Barcelona, as a token of gratitude for the help Charlemagne had given him four years earlier against the Vascons, when he had to retreat through the Navarrese pass of Roncesvalles.

The court marvelled at the chess set, which was made by Arab craftsmen. The pieces showed signs of their Indian and Persian origin. The chessboard, forged in silver and gold, measured one metre on each side. The pieces were made of filigree precious metals, inlaid with uncut diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds. Because of the brilliance it seemed to glow with an inner light that mesmerised the beholder.

According to legend, Charlemagne, influenced by strange effluvia coming from the board, proposed a wager consisting of the following:

If the soldier Garin wins a game, I grant him the territories of my kingdom, which stretches from Aachen to the Basque Pyrenees, and the hand of my eldest daughter in marriage. If he loses, he will be beheaded in this very courtyard at dawn

.When they had been playing for more than an hour and with convulsions and excitement, Charlemagne sat up with great effort and threw the board to the floor as if freeing himself from a curse, the pieces fell to the ground and the game was interrupted.

According to those present, the game was abandoned, as they considered that the chess was possessed by an evil force. However, on a less tense note, a new game was started and Garin triumphed and received as a reward the property of Montglane, in the Lower Pyrenees.

Drafting the text: Roger Salvo

Escacs i escacs -

Chess game for the hand of Matilda of Germany, Countess Palatine of Lotharingia

Ezzo, Count Palatine of Lotaringia, won his wife, Matilda of Germany, Countess Palatine of Lotharingia, in a game of chess. He played against her brother, Otto III, for her hand in marriage, and won.

Otó II rebent homenatges de les províncies, simbolitzades per dones germanes, franceses, italianes i alamanes. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Silvestre II en l'Evangeliari d'Otó III Meister der Reichenauer Schule, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons -

-

The 14th century crisis

Little Ice Age (1300 - 1250)

Black Death (1347 - 1354)

Subsequent refeudalisation

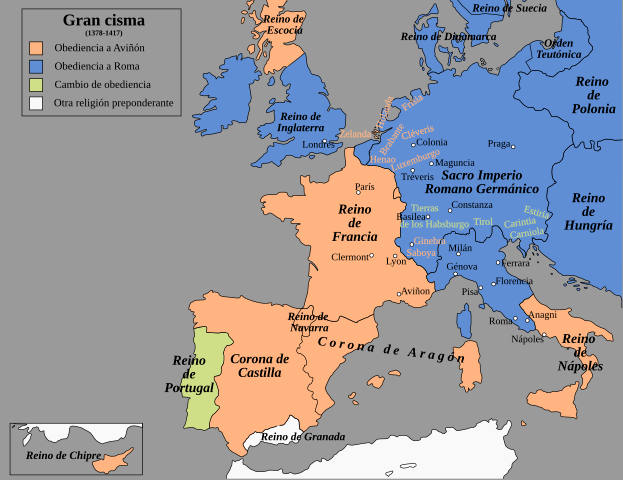

Avignon and Western Schism (1378 - 1418)

Division of Europe during the Western Schism. Some kingdoms gave their obedience to the Pope of Avignon (in orange), others to the Pope of Rome (in blue) and others, according to convenience, changed sides one or more times. @lankazame, Mipmapped, rowanwindwhistler, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsFall of Constantinople (1453)

Golden Horn Chain Photo: David Berkowitz from New York, NY, USA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Regne de Sicília MapMaster, Rowanwindwhistler, Indpcatll (this version), CC BY-SA 4.0, via la Wikimedia Commons.jpg)

Andronikos II Palaiologos, Byzantine emperor (1282-1328) Byzantine art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mehmed ll, Entering the City of Constantinople Fausto Zonaro, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons